For this project, we are asked to read and make notes 1920s article by Osip Brik, Photography versus Painting, then answer three questions. The notes are included as a separate post under Reading. In this post, I consider the three questions.

Do you think that Brik's article points to a practice that was taken up by photographers or other artists to any great extent?

To summarize, Brik's most important points:

- that painters cannot hope to represent reality as well as photography - in this respect, painting is the 'horse and cart' and photography the 'automobile'.;

- photographers have an important social role that they do not realize;

- photographers should not seek to "attain the social recognition of painters" but to accentuate the difference: “By

battling against the aesthetic distortion of nature the photographer acquires

his right to social recognition, and not be painfully and uselessly striving to

imitate models alien to photography.”

In short, photographers should stick to the knitting and develop their craft in a distinct way.

It is important to see Brik's article in context, both in terms of its timing, and that he was Russian. The camera was developing quickly in 1920s, becoming smaller, lighter and faster to use culminating in the invention of the first 35mm camera by Leica in 1925 (Badger 2007, p68). This meant photography could more responsive to the immediacy of a situation, requiring minimal set up, and therefore ideal as a reporting medium. Russia was in throes of optimism post the Revolution; there was a perceived need to record the new socialist existence.

For both these reasons, and, one suspects, a reaction against the perceived bourgeois nature of 'painterly art', that Opik sees photography as different, not really an art at all.

His approach was one of the strands of what has been termed 'The New Vision' an eclectic approach adopted in Europe in 1920s (Badger 2007, p59) with the common feature of using the lightweight camera to take photographs from unusual angles, vertically and extreme close up. Of particular relevance to this article was the strand termed Russian constructivism expounded most famously by Alexander Rodchenko and El Lissitsky, both of whom, significantly, were typographers, artists and graphic designers as well as photographers.

Rodchenko declared painting dead and turned to

photography - art was bourgeoisie. For him, the camera was the tool of new man (BBC, 2007) . He

even wore a special uniform. He explored his constructivist ideas within the propaganda framework, such as this image of people walking to a politically approved demonstration. Perhaps ironically in view of the politicalisation of the image, it fetched £46,100 at auction (Christies 2007)

|

| Assembling for a Demonstration,.1928 Alexander Rodchenko |

El Lissitsky embraced constructivism enthusiastically. He repudiated traditional art as bourgeois and decadent, and embraced photography, typography and film which he believed would be a new art for a new age; he was the archetypal 'artisan' as opposed to 'artist' as described by Brik. Lissitisky used collage in this self portrait, where vision passes from head to hand, itself holding a compass as a symbol of the scientific basis for the new world order (Badger 2007, p59).

|

| The Constructor, 1924 El Lissitsky |

The constructivist philosophy was clearly associated with Brik's article, perhaps to the point where it may be viewed more as the cause of his essay than the result. But constructivism was just one of the manifestations of New Vision, an umbrella philosophy that was politically motivated and was inclusive of several related disciplines.

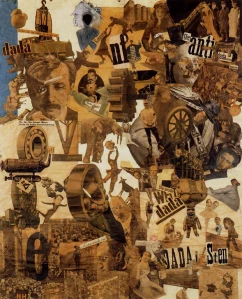

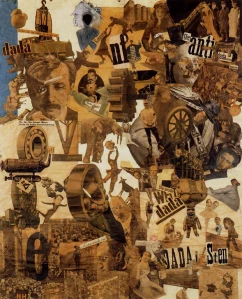

Surrealism was another manifestation of New Vision thinking. Born from the nihilistic, anarchic Dada art movement (later associated with Anti Art, thus the link with Brik's article), surrealists investigated the unconscious world (Badger 2007, p63) and were taken with photography, partly because it was perceived as an antidote to bourgeois traditional art. Photomontage was one popular medium, this image by Hannah Höch being one of the most well renowned, containing politically overt icons questioning the Weimar republic and women's place in society:

|

| Cut with the Kitchn Knife, 1919, Hannah Höch |

Lastly, the typological approach, the production of many photographs of the same thing, emerged in 1920s. This approach can be seen in part as the development of photography as its own discipline, simply because the production of multitudinous images was physically beyond traditional art. The photographer was thus 'acquiring his right to social recognition' to paraphrase Brik. Typology saw the emergence of the photobook, both non political as in Blossfeldt's Art Forms in Nature, an unintentional photobook resulting from Blossfeldt's work on the sculpture of living, and political, as in the images of Sander. His book Man in the Twentieth Century. Face of Time attempts to classify contemporary German society, an example being this image of young farmers, an outstanding social and psychological image that leaves the viewer questioning the activities, expressions and gestures of the subjects. It is documentary photography of the highest quality and is therefore a fine example of why photography should not seek to 'strive to imitate models alien to it' as Brik says; the image stands on its own without comparison to another art form.

In conclusion, I believe we can say that Brik's article does point to practice that was being adopted by a number of related approaches all of which were overtly political, and all of which were empowered by the improving technology of the camera. Brik was making a point - "don't worry about art, go your own way photographers" - but it was happening anyway; he hardly needed to make the point.

Do you find any resonances with Brik's ideas in contemporary discussions of photography and painting?

Contemporary discussion has tended to focus on the status of photography as an art form. Wells (2006) uses the distinction made by Williams (1976) between 'art' as a creative skill and 'Art' as fine art practices - being shown on exhibitions, galleries, museums, for example - to point out that the medium has more typically been viewed as the former than the latter. It was not until 1989 that the Royal Academy had its first ever photography exhibition. The Tate Modern's first photographic exhibition was 14 years later. In crude monetary terms, the most expensive photograph ever is Anderas Gursky's Rhine II which fetched £2.7m in 2011; comparing that to the $58.4m that Ballon Dog: Orange was sold for two years later (as per previous post) provides an indication of the respect of relative merit of the two artistic media.

Howells and Negreiros discuss the argument of Roger Scruton at length. Scruton's view is uncompromising: there is no beauty in photography except insofar as reflected in the subject - the photographer adds nothing whereas "a painting may be beautiful....even when it represents an ugly thing." (Scruton, 1984). This is surely too simplistic; given the same subject in the same place at the same time, a group of photographers will undoubtedly produce very different images whether by using skills that are familiar to painters such as composition and use of light and texture, and by using more technical skills such as experimenting with different focal lengths or focus points. The photographer can add beauty where none may be evident in the subject.

These arguments are resonant with those of Brik but come at the central core of the debate form a different angle. Whereas Brik was all for celebrating the democratisation of art by the new more accessible medium, Scruton is scornful of photography's claim to be art because he implicitly believes photography wishes to be seen as an equal to painting. His viewpoint that celebrates High Art is entirely different to Brik's.

It seems to me that photography protests too much. Photography in an artistic sense suffers because of its very success. Everyone has a camera. To quote Walter Benjamin:

"The illiterate of the future will not be the man who cannot read the alphabet, but the one who cannot take a photograph."

This is perhaps an extreme view but it emphasises the accessibility of photography, even more so in these days of camera phones and tablet computers. If you take 500 photos on holiday, you are virtually certain of taking a few that are very good, if only because you get lucky on composition and the structure of the subject requires little technical input. But does that qualify as art? Is the photographer actually interested in whether it is art? Therein lies the crux of the problem for photography: it is used for many purposes, most of which are at best tangential to artistic motives. Photography is used in endeavours as varying as forensics, advertising, sport, and documentary; in none of these is the artistic quality the prime motivation of the photographer even though there may be artistic quality as a by product. There have been attempts to use images captured for one reason to be used as an art form - for example, Weegee used his position as a press photographer in 1940s New York to follow the emergency services and capture strong black and white images that became exhibition material - but they are the exception. The variety of uses for photography and the sheer amount of photographs taken inevitably means the boundaries will be blurred between what is photographic art and what happens to look good artistically despite being produced for a different reason. The tendency for photographers to produce photobooks or series of images as artistic works often combined with text (e.g. Short 2011, ch4) perhaps is a result of the need to differentiate the medium as an art from from one that is utilitarian. Painting has less need to consider this dialectic, there is a stronger distinction between painting as fine art and commercial art.

As a footnote look at the voting and arguments on Debate.org. As at 25 January 2014, the voting on whether photography is art is split exactly50:50. This argument evidently has a way to go.

Find and annotate two examples of images that demonstrate the impact of photography on painting

In order to carry out this exercise I performed an internet search on "images demonstrating impact of photography on painting".

Some interesting links appeared of which Sozanski (1999) was one. He writes about an exhibition of artwork directly based on photographs at the Synderman Gallery in Philadelphia.

Of those discussed, I selected Mobil by Peter Cain as the first image.

Cain has taken a photograph of a day to day scene and extracted the signs, text, numerals (Sozanzki calls it 'denaturing') and translated to a painting that is now a geometric pattern of colour, an image of symbolic, semi abstract resonance. One gets a feeling of space and emptiness that would be absent from the original photograph.

The second image is The Jockey by Degas. This is an early example of the direct impact of photography on painting. Degas used photographs and reflected the gait of the horse and the action of the rider in pulling the reins back.

Conclusion

I found this project interesting and rewarding. The argument about photography's place in the art world has been raging for over a century and this project was a chance to consolidate my knowledge and thoughts on the subject, and then to look at the subject from the point of view of painting and how it has been directly impacted by photography with two examples.

References:

Badger (2007) The Genius of Photography. Quadrille Publishing Limited: London

BBC (2007) The Genius of Photography. DVD.

Benjamin Quotations from the World of Photography Available from http://www.photoquotes.com/showquotes.aspx?id=160 [Accessed 24 January 2014]

Christies (2007) Auction details Available from http://www.christies.com/lotfinder/photographs/alexander-rodchenko-assembling-for-a-demonstration-1928-4983498-details.aspx [Accessed 20 January 2014]

Howells and Negreiros (2012) Visual Culture. Revised 2nd

ed. Cambridge: Polity Press

Scruton (1984) The Aesthetic Understanding Methuen: London cited in Howells and Negreiros (2012)

Short (2011) Creative Photography Context and Narrative AVA Publishing: Lausanne

Sozanski (1999) Assessing Photography's Impact On Painting Available from http://articles.philly.com/1999-03-12/entertainment/25511640_1_painting-photorealist-photographs [Accessed 25 January 2014]

Wells (2006) On and beyond the white walls Photography as art In Photography: A Crtical Introduction Third Editon Routledge: Oxon

Williams (1976) Keywords London:Fontana cited in Wells (2006)